(hotd) the rapture of that cruelty which yet is love

Fandom: House of the Dragon

Pairing(s): Alicent/Rhaenyra, Daemon/Rhaenyra

Rating: Explicit

Length: 35k, 1/1

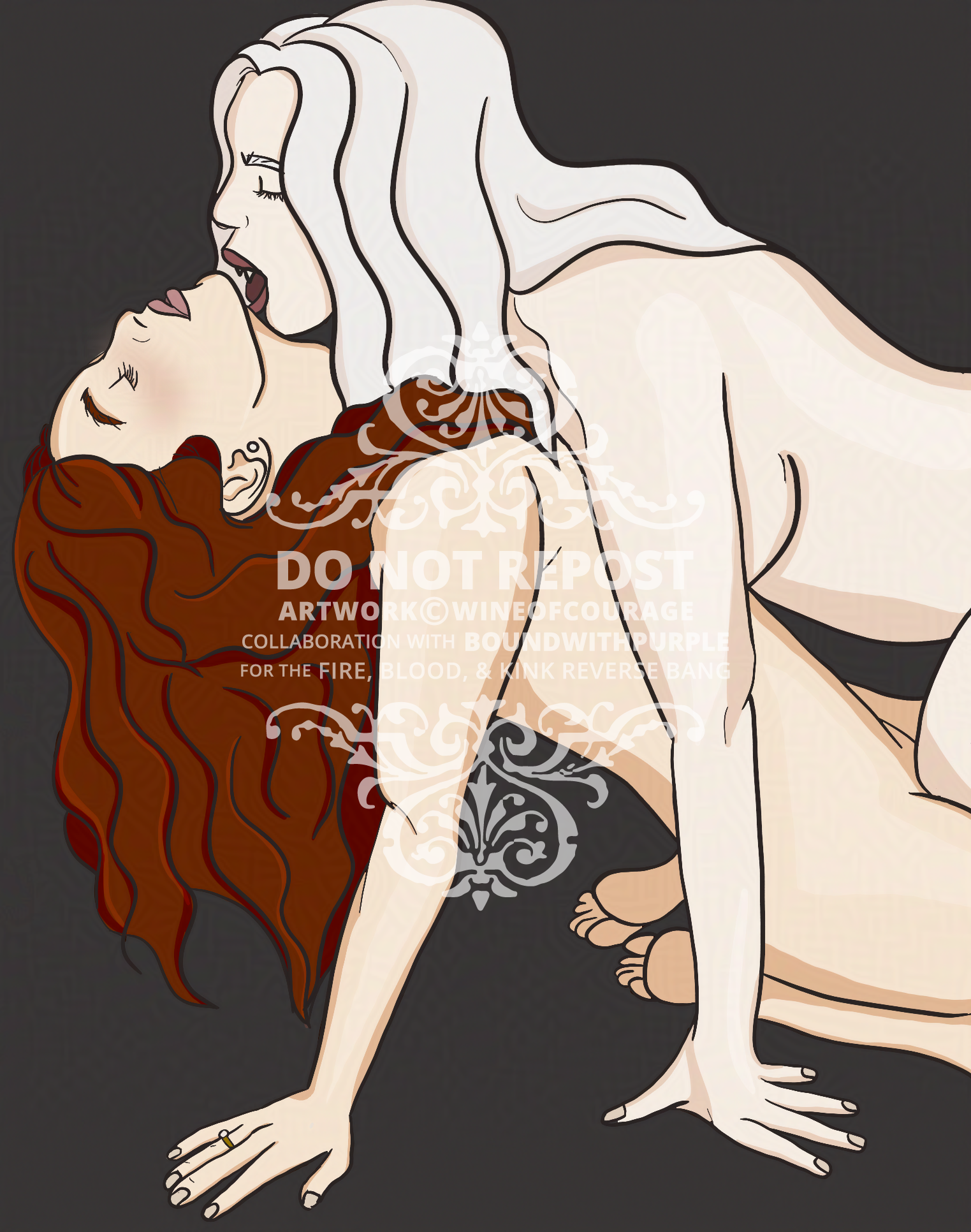

Tags: Alternate Universe - Victorian, Vampires, Gothic Pastiche, Frame Narrative, Uncle/Niece Incest, Sexual Abuse, Rape/Non-con Elements, Dubious Consent, Blood Drinking, Vampire Sex, Lesbian Sex, Embedded Images, NSFW Art

Written for the Fire & Blood Kink Reverse Bang.

Summary:

Rhaenyra died when Alicent was fifteen. Now, almost twenty years later, Rhaenyra has returned looking not a day older than fifteen—and speaking fondly of something queer: bloodlust.

Content warning: the “sexual abuse” tags refers to an adult vampirically feeding on a minor—no human sex happens, but it’s an intensely erotic and eroticized act and experience that qualifies it as such; this is my attempt at a Neo-Victorian narrative/pastiche in a Victorian Era/Westeros mashup and although it’s relatively minor the general vibe contains some Orientalism, colonial mindsets, ableism, fetishization of paleness/white skin, admiration for the vanished glories of civilizations that were brutal slave empires, etc.; lastly it’s a vampire story with all that might imply about consent issues, as well as specific themes of predation/underage predation/fixation on eternal girlhood or youth etc.

Acknowledgments: Thank you to Becca for her gorgeous art and for being a lovely collaborator, and to all the event staff for their hard work that made this such a well-run event that was a joy to participate in every step of the way!

“In the rapture of my enormous humiliation I live in your warm life, and you shall die—die, sweetly die—into mine. I cannot help it; as I draw near to you, you, in your turn, will draw near to others, and learn the rapture of that cruelty, which yet is love...”

—Carmilla, J. Sheridan Le Fanu

Twenty-seventh day of the tenth month, 1875 AD

Dear Mellos,

Enclosed with this letter is the copy of an astonishing narrative related to one of my cases; the patient somehow managed to smuggle this document onto the ward and hide it under her mattress for a week before a nurse discovered it. I trust you will forgive the poor manners of the abruptness of this opening, both from your usual sympathetic friendship, and from the understanding of the degree of the shock I have suffered that sympathy will quickly form upon reading what I have sent you. I dare not discuss this with any colleagues at the hospital. I knew the good lady who wrote these words intimately—as will not surprise you upon seeing her maiden name, for so did you know her then, in your occupation of the position I replaced you in on your retirement—knew her hand by sight—can attest that it was none other than she who composed this revolting tale, as much as it pains me that my honesty, and concern for my charge, binds me to so attest.

But I do not wish to taint the reputation of a woman of true virtue and keen intelligence, as you yourself know well, who labored so tenderly on behalf of her children, nursed her husband with such devotion, and led a great household with wisdom, and it is for this reason I burden you, and trust to your discretion. These stresses, of a character as must have tried the health of even a woman of her mettle, surely account for this disturbed fiction, penned in her last days. She must have been far more ill than she had let anyone see, and the impression that her mortal sickness was very sudden an illusion. Poor woman; the burn marks on the edges of many of the pages show that some part of her resisted whatever morbid demon of the mind had taken possession of her, and she repented of what it had compelled her to write.

She did not wish her daughter, who I also know was surpassingly dear to her and much attended to (the hospital, whose management I had taken over since my friendship with the family, was chosen for the patient’s care because of our correspondence about the child’s fragile spirits) to actually be the recipient of this filth. Alas, if only her strength had sustained her to destroy it before she did! It must be this that has done for Helaena’s—that is the girl’s name—nerves. Before, to my understanding, although she was worryingly delicate, she was also a happy child, but no longer. She fought like a fiend when these pages were taken from her, and swore that her mother, dead these three years, would be back for her. That is all I shall write for now, I will not take up the time you might better spend reading that which is necessary for us to have a deeper conversation about this case which oppresses me. I take the liberty our long intimacy and my respect for your opinion I think allows me to urge you to read it with all haste, and write me when you have, so I might receive the succor of your advice.

Yours,

Dr. Orwyle Orme

-

You never inquired about your sister. Not once in your childhood did you glance up from your embroidery and find your attention ensnared by the portrait above the mantel in my little green parlor and lisp, “Mama, what a charming girl she appears, with those lovely, lively eyes with their striking bold look, that makes one fancy she might step down from the wall any moment—is it very like? What was she like, my sister, for I never knew her…”

Perhaps you sensed your father’s injunction, itself unspoken, that she should never be spoken of; for somehow despite the lack of an explicit order from its lord and master this prohibition lay over the whole castle with a powerful force, as if it bound the whole place in a solemn oath of silence. It was remarkable, I’d always thought, how this interdiction I felt to stop my own tongue and seal my own lips was even so absolute as to extend to explaining a discovery I once made, that such a delicious fount for the tattle of servants was apparently never tapped belowstairs.

-

I discovered it one blustery winter afternoon, when, several months after she’d come into my service, I chanced to dart my eyes, wearied from the rapidly fading light, up from the correspondence they strained over—letters to my family in Oldtown announcing the birth of Daeron, I seem to recall now—to ask Talya to light the lamps, and found her staring at the portrait above the hearth.

The girl was so arrested by it she’d ceased the dusting that was her task, of whatever of my poor ornaments on the mantel had survived your older brother’s depredations—a dashing bravo bowing to a masked courtesan wrought in Myrish glass, a vase from Yi Ti filled with golden hothouse roses, a painted figurine of the Mother with one child perched upon her knee clapping his fat dimpled palms together and one leaning her sweet smooth cheek on her shoulder—some of those pretty little things I had placed about the chamber in an attempt, of which some tapestries inherited from my mother depicting scenes of a springtime wood in the Reach where fox-kits tumbled on beds of new grass beneath budding trees thronged with songbirds, was a chief part, and which gave the room its name, those being the only source of decoration available for the stone walls, to brighten a gloom so pervading it was not even dissipated at the hour of peak illumination afforded by the westward windows, for there was nothing fine or delicate that was not at risk of finding a piece of itself broken off in Aegon’s careless, fidgeting hands.

Anyway, as I said, when I lifted my gaze from my task, which the gathering dusk had plunged into such obscurity I could not continue it, or finish it before supper, without adequate light, it halted upon a sight that made my blood run queerly cold. My newest maidservant stood unmoving, arms slack at her sides and the cloth she had been using spilling from the tips of her limp fingers, her eyes riveted upon the painted ones in the portrait. No, not quite entirely still, and it was this that made that bolt of ice thrill up my spine: Talya only appeared as motionless as the figure in the picture in that instant my attention shifted upward from my desk with her name upon my lips, and the vision imparted was enough to make the word die there, and the amendment which followed as my brain tried to make sense of it made my throat too dry to revive it.

Yes, her feet were stuck fast to the carpet, and her hands were not engaged in their usual flutter of tidying, pouring, folding; each individual part of her was immobile as stone, as if she had been paralyzed by some venom—but her whole frame, her body as one unit entire and greater than the sum of its parts, swayed slowly back-and-forth, as if she was a stem stirred by some impossible breeze in the closed apartment, and yet as if the stalk must assent, bend willingly, go pliant in a flirtatious dance with the wind that would lead it; or, rather—this was the unsettling thought that came first before being ordered into words, which put into my mind the unsettling, unaccounted for idea of some poisoned bite working upon her limbs—it was like the Dornish snake-charmer that we’d once seen at a fair in Spicetown.

We’d watched the man imitate the snake’s sinuous writhing as it emerged from a basket to the caterwauling of a bone flute, and it was unclear to me if it was indeed the music that effected the trick that had us tossing coins in a hat after the snake had been beguiled back into the basket again, or if it was instead its own undulations reflected that mesmerized it and forced its performance of a safe snakishness. This was at first puzzling, for what in the silence of lifeless pigment could work so upon living flesh? Then horror had me in its grip as it became not at all odd, and the only mystery was my abrupt conviction that it was the enchantment the portrait had cast on its viewer which in turn had but temporarily tranced image into holding the lines the painter decreed, with only a certain rippling flash in the gleaming pupils granting a glimpse of what had been compelled to an abeyance of a deadly strike.

“Talya! By the Seven, what do you think you’re doing? Are you blind? Do you not see how dark it has gotten? Stop dawdling and light the lamps at once!”

When my tongue finally revived those stillborn syllables, they were expelled far more harshly than I had originally intended and followed by this bilious flood, for I was pricked by an urgent need to break the air of witchery that had my nerves painfully ajangle, while also to deny it. I played the stock part of mistress scolding maid, one I had never before that day so confidently inhabited, because as a new bride and even then, married for nearly a decade and a mother of four, it was difficult for me to believe myself truly a wife, and not an overgrown child filling in, and laughably, a role once performed with effortless perfection by my predecessors.

Though my reproof was delivered in a tone of command that sounded more convincing than usual to my ear, my unease deepened almost to dread when it seemed for an awful span as if this counterspell for whatever had she at whom it was cast in thrall would not work, because for long heartbeats she did not turn at the incantation. I could not effect that magic order a woman in full possession of her powers could weave upon her domain for the felicity of all who resided within it, nor achieve the grateful submission that would counteract any weak-willed, morbid fancies, of the kind exacted by the grace and elegance of my own mother, or the warmth and gentleness which was my husband’s first wife’s gift, and I myself had observed made all hearts love her.

But even my feebler capacity had some force. After those shuddersome seconds—it could not have been more than that—where the world narrowed to the white of her unbent nape, she stepped back, but with a bizarre wrenching motion, facing away from me for a further interval before whirling around with a gasp. She blinked as if truly waking up, and unsure of where and what she had awoken to.

“Your pardon, ma’am—I am sorry, I don’t rightly know what came over me, what—?”

“The lamps, Talya. The afternoon has grown quite dark. Unless you are unwell—”

“No, my lady,” she insisted. “I’m quite well. Right away. It’s only—”

There she paused, as her head turned on the stem of her neck but did not complete the circuit, and I thought I discerned a willful halting in the way her chin dipped to brush her shoulder before she straightened up and bustled forward toward the lamps.

It was only once she had them merrily burning, distributed around the circular room in a ring—mantle, end tables, my desk—that, blowing out the match and watching herself fiddle with the dial on the last to make the flame flare brighter, she picked up the thread that I, shaken, had let her drop with relief.

(That room, or any other in the grim old fortress, could never be said to be truly cheerful, but at that specific narrow time between afternoon and evening when the lamps were lit, on an overcast winter’s day, it was as if the walls were very permeable, with its location on the top floor of one of the massive towers, thrust up into the air, suspended over the waves above, but also impressed on one the keen sense that the walls were there, and one was dry and warm and unbuffeted by the winds one heard scraping stone, brought by the luster of the lights holding back the gray mists of clouds and seafoam drawing in night.)

“Ma’am,” she began, “I’d never really taken note of it before, but I found myself wondering—who is that lady there, in that picture that hangs above the hearth?” After a start that was deliberately casual in tone, her query ended with her words tumbling over each other in a rush, and she blushed. “Pardon me,” she mumbled, “it’s quite impertinent, I know—”

“I would say it is!” I intervened sharply.

Talya had been an excellent addition to the household staff since her employment with us commenced, and I was surprised at this unforeseen display of a crass penchant for gossip, and dismayed at the brazen ill-breeding evidenced in going so far as to play at a laughable ignorance in trying to acquire it. For I truly thought that it was not feasible she did not know the identity of the sitter in the portrait, and that such a question must be low pretense. A daughter of the house, cruelly taken by death in the flower of youth—following mother and infant brother to the grave not even a year after that dual calamity—could this fail to be featured as a subject among the talk that whiled away the after dinner hour around the fire in their parlors? It was impertinence indeed, and I was icy with affront.

I perceived, from the way her complexion went from pink to red, that she was sensible of the chill in the atmosphere, but this blaze suggested the stoking of an inner heat that allowed her to bluster forth into its blast.

“It is only that I have never before served in a grand old house like this, nor even passed through the gates of one before the day I took up my service here, and to go about my work beneath the likenesses of personages from so long ago looking down upon me from their frames, sometimes it seizes my fancy, as I can’t help thinking of all the years that these walls have stood, and how those lords and ladies once walked through these halls as I do, but in the course of lives so very different from mine, so—romantic, I suppose, or so we always found them, in the kind of stories we heard when I was a girl, and I couldn’t help but wonder which one she was…”

She trailed off at the disbelief that showed plainly on my face. If I could have controlled my features, I might have admonished her that though the tales told of my husband’s ancestors were lurid, they were much exaggerated, and the portraits in their browning varnish depicted men and women who were once flesh and blood like she and I and despite the unorthodox and exotic practices they had brought with them to our shores and held on to until, admittedly, more recently than it was comfortable for many to contemplate, they had for centuries in most particulars conducted themselves like any other noble lineage in Westeros, and were not the figures of black magic and brigandage from foolish old women’s fireside tales.

(I was not confident this was true. After all, I could still vividly recollect, if not the first time I myself walked beneath those painted observers, the first time that mattered, with the powerful impression of being judged by their fierce gazes, which brought to mind a trip to the zoo in Oldtown on a visit back—a visit I could no longer remember in itself, only remember that memory which transmitted it indelibly, by the association that subsumed it—where I’d seen a creature in a cage there with the same smoldering hateful eyes. I knew even then they were only pigment, of soot and bone black for pupil and gypsum and lime for sclera and more complex mixes of azurite and cinnabar for iris, even if I had not yet been taught the names of the materials that made up the varying tints. That same trapped fire that hated its confinement in oils no less than within bars and hated me for being walking free before their imprisonment, for being alive, when they were not.

And the hot hand in mine tugging me from likeness to likeness and introducing me with a lack of any shyness, with the total familiarity one has with those which one converses with every day of one’s life, and despite the introductions featuring narratives of murder and ravishment, not only with none of my strangling terror that their hands would burst from their frames to rend her with their nails, but with a conviction that Rhaenys with her scandalously low neckline of the previous century and the beauty mark and her tumbled powdered curls and mischievous smile and her little silk slipper loose at the heel on her adorable foot, and Visenya stern in a hunting habit with a pistol at her belt, standing at a desk, one hand extended with its forefinger finger pointing toward a map and the other on her son’s head, and Rhaena with a complexion pale with grief and defilement in her widow’s weeds, if they escaped their incarceration, would reach out to pet silver hair with thin burning fingers, draw up into black-damasked laps turned yielding for this occupant…

But despite the biographies given to me that day with perfect childish matter-of-factness, the contention that his grandfather always asserted they were the equally childish fantasy created and cherished by the lower orders had been my husband’s damper on what he maintained was giddy, girlish ghoulishness.)

My mouth was, however, too idiotically agape for such a venture and could only shape itself to exclaim, “Why, you really don’t know!”

Yes, she really did not know. I asked her if she really could confuse the fashions of a decade ago with those of the past century, and moreover, did not see the resemblance with the portrait of Lord Targaryen’s previous wife which she had perhaps seen when she brought us tea in his study, which told the truth of the identity of the sitter in this one, which I now informed her of. Talya assented that yes, she could see the similarity now, and the modern make of the white dress the girl in the painting we discussed—she remembered when she was a girl, that ladies had sleeves like that—but in a tone of doubt, that suggested she was trying to convince herself of facts that contradicted whatever had cast its spell on her, something quite beyond fact, and impenetrable to it.

-

I was so cross with her that afternoon because she was late in her dusting that day for some unimportant reason I cannot recall. Usually at that hour I was alone, and this was by design. I had set down my pen and looked up. Typically the lamps integral to the ritual were already lit. For a matter of minutes, or up to a half hour sometimes depending on how recalcitrant or docile she had decided to be, the shifting balance of my strength versus hers, we would stare at each other. It had to happen at that time, which changed through the year, requiring calibrations that the staff struggled to keep up with, that specific thin line between light and dark. By daylight it was simply the insipidly pretty portrait of an inspidly pretty girl, amateur, painted a decade ago by yet another insipid miss under the instruction of their drawing master.

By night, it became something else. I did not know what—I made sure never to be in that room at night, under the excuse of how it became mysteriously difficult to heat adequately once dark had fallen. I only understood I had put something into this, my first and last work of portraiture, made in my fourteenth year, which I did not understand, and which could not simply be destroyed and was thus my singular responsibility, and which consigned me to wrestle it back into the slumber it seemed to struggle out of each night as the candlelight glinted a secret amusement into the eyes and made the red gem at the center of the necklace of Valyrian steel pulse like a heart.

-

I was born in Oldtown, chief city of that region of wine and honey, the Kingdom of the Reach, but my earliest memories were of shale and gale, because before I had reached my first year my father had relocated his family—save my elder brother Gwayne, left behind under the care of my uncle, to reap the benefits of the excellent education the famed schools there could provide, as well of those of his relation with so preeminent a guardian which was an advantage that could not at that juncture be scorned—from that scene of sophistication to be an outsider in the bleak landscape and cruder society of the Kingdom of the Stormlands. This move was done in pursuit of accruing benefit held in his own right and by his own ability, and in his own grant to bestow upon his young family, preferring this to remaining at ease and in esteem in a venerable homeland but enduring a dependence that an intelligence and pride such as his could not help but experience as intolerable indignity.

He was the younger brother of Lord Hightower, had studied law at the Citadel, the most prestigious university in all Seven Kingdoms, and put it to the use of his family for many dedicated years. He had resolved not to wed or start a family until he could support it from his own enterprise rather than his brother’s magnanimity, and he married my mother and fathered my brother and I well into his middle age. Once he had children of his own, however, he desired not only to provide for them in the present but in future, to create a legacy he could bequeath them. The Stormlands were, in those days, still a wild and more sparsely populated place, lacking the cosmopolitan cities of remotest antiquity and the heights of culture of the Reach, or even, in the same numbers, the thronging ports, and bustling market towns, and pretty villages studding the dense, old cultivation of sprawling farmsteads, that the Riverlands and the West could boast. It was not as remote or desolate as Dorne or the North, and my father guessed that though our new home was rough and undeveloped, that only meant it was ripe for development, if a man fit for the task set his will to it.

By the time I had reached the age when a child begins to grasp the circumstances of her life, I knew the facts that had made me Rhaenyra Targaryen’s special friend: my father had arrived in Duskendale, the largest town and economic heart of the Stormlands, and with his capital formed the company that built the first railroad connecting that port—which was the point of arrival for perfumes from Lys to dab at our throats and wrists, lace from Myr to adorn our hems, amber and furs from Ib to encircle our necks and arms and warm our shoulders, and whale oil to light our lamps and whale bone to sculpt our waists—to Oldtown’s, whence flowed in spices from Qarth to season our food and gemstones from the Summer Isles to bering our fingers and stud our ears, and gleaming hardwoods to plank our floors and and be carved into chests and cupboards to contain these commodities, and into ladies’ dressing tables and dining room sideboards to display those from even farther afield, jade statuettes from Leng and silk runners from Yi Ting. In the course of this endeavor he made first the acquaintance, and then the friendship, of many of the most prominent families of the realm, including the Targaryens of Dragonstone.

It was only natural that a man of my father’s ambition should seek an intimacy with Jaehaerys Targaryen, as it was that one of Jaehaerys’ make should respond with interest to the overture. He was the greatest statesmen the Kingdom of the Storm had ever seen; it was he who as Chief Minister to several Durrandon kings had sown and nurtured the seeds of progress that my father would harvest, had in concert with the influx of wealth Corlys Velaryon as Admiral and his expeditions brought taken his family’s adopted homeland—for though it had been nearly a thousand years since they arrived on that shore, still, like us, they were in some way outsiders—from a wind-wracked, pirate-plagued irrelevance to a state of unprecedented prosperity: taxes imposed; roads laid; streets paved; schools founded; levees built; canals dug; marshes drained; laws enshrined.

This miraculous transformation was matched by the one this record of service effected in turn on his family’s reputation, so that even a man as conscientious about the proprieties as my father felt no qualms about any ill-result attending a young daughter’s moral character as a result of the association. It was rather a testament to the redoubtable strength of the famed character of this patriarch that his own origins, both his ancestors’ histories in the centuries since they had claimed the isle that was their seat and the many tragedies of his own early life, were filled with such outrages as begrimed his family tree. The murderous feuds between close kin, the incestuous “marriages” that besmirched the legitimacy of all children born from them (his own marriage to his cousin—daughter of the usurping uncle that had murdered a brother and turned a sister into his illegitimate bride—was nothing uncommon): that had been consigned firmly to the past by his towering reputation for probity, duty, and virtue.

The period of this formative relationship proved brief, though far more decisive that its duration might appear to warrant. The friendship between that reverence and my father lasted only a year before death from advanced age took him. He was succeeded by his grandson. He had been plagued by heartbreak in his children, both tragedy and dishonor. Promising sons preceded him to the grave, as had most of his daughters, and the name of the one remaining to the world of the living never passed his lips. For scandal had not entirely been extinguished from his line—merely reduced to a kind that might visit its affliction on any honest man, no matter how unimpeachable the management of his household.

Jaehaerys’ heir was of a quite different character than his esteemed grandsire. Amiable, good-humored, and preferring the quiet joys of domesticity with a much loved wife to the strivings of the world, he was not completely lacking in ambition, but it was of such a moderate type that it could not overcome a lack of inclination for the forceful effort that must support the attainment of its goals, and his disposition was of such a cast that any disappointment at this was so slight as to not be much noticed by anyone with less fine a discernment of men’s natures of than my father, who noted, and had corroborated once he swiftly acquired Viserys’ confidence as he had his predecessor’s, that pangs of disquiet at falling short of the legacy he inherited with name and castle were not strangers to him, although neither could they say to be intimates. It must have been a puzzle to those who follow and comment upon these matters that my father should have maintained an equal warmth of intimacy with one who at that date could not have appeared to offer much in the way of an advancement he could not even secure for himself, and although the discovery, several years on, of the uses of dragonglass in powering steam engines amply justified this loyalty, if urged to honesty, I must admit it owes to the luck that has assisted inborn talent in the successes of my father’s career.

These were the circumstances that I was aware of, in the vague, distorted fashion of childhood, or came to be aware of, as those that had designated me as a sacrifice, in that year I fervently believed that that was what I was to be.

Strange, that I do not remember my first day on Dragonstone or its first meeting with Rhaenyra. But if it transpired the way it was told to us, as our mothers later occasionally laughed over it, it must have played its part in the surmise that was to overtake me with a conviction that I certainly did not experience as ridiculous at the time. As I, aged six, peeped out from behind my mother’s skirts, the shining petite presiding priestess of the place apparently jumped up from playing with her dolls on the rug before the hearth, came forward boldly as I would soon come to know she always pleased and hauled my timid self out, inspected me with her presumptuous palms (plucking at my pinafore, fondling my plump arms) and staring searchingly into my eyes as a smile stole over her lips, before thrusting her hands under my curls and reportedly sighing, “O, but she is beautiful! Even better than the whip…”

That was the anecdote that was fondly chuckled over, Rhaenyra’s darling daring and my adorable apprehension, but I am sure Lady Targaryen quickly tugged her daughter back and chided her for rudeness, apologized to my mother, who no doubt insisted that of course Lady Rhaenyra had caused no offense, it was only natural she would be so excited to have a new little playmate for company. Another thing it seems I had always known, for I could not say when it was I was told, and likely never was, it being the sort of thing picked up by children—who are so sharp in deciphering that which is left only to implication, for that is precisely what rules small lives—was that I was a gift my father offered up to Lord Targaryen’s daughter.

It was said, I think, because despite the rest of that introduction proving irretrievable to my conscious memory—the dolls are my embellishment, the other details reportage—I could still hear Lady Aemma’s sweet voice crying the words, “Darling, look! Mr. Hightower has brought you a friend,” perhaps because they tied themselves to other associations, as I will reveal shortly. It was all that lay behind this simple utterance that I must intuit.

That Rhaenyra had to be brought friends in her isolated abode; that she would be brought them because she was a special sort of girl; that she was in this isolation because the family did not often travel to town, and this was because her mother was often ill; that she was so often ill because she was always having a baby and the babies were always dying, so the spirit of the place was sad and the daughter of the house was too; that she had no playmates because she was the only occupant of the nursery, till I came. That I could please my father by becoming this daughter’s intimate, as my mother was meant to become its lady’s, although they never got on, quite, and anyway my mother was not at Dragonstone nearly as often as I was, with my long stays with their shared schoolroom under Septa Marlowe’s tutelage, having her duties as my father’s hostess, and as he himself had become a confidant and guide to its uncertain lord; that this might be of some benefit to him later.

Such a bosom friendship was a part of the strong threads of connection I was to help to spin, one that might be densely woven as we grew to womanhood, binding fathers and husbands and offspring in one fabric through the gentle genius of female amity, even if it was no son and heir for me to secure the infant affection of, that it might be nursed to its fuller form in maturity: for another thing I apprehended was that she, this girl who seemed so natural to the environment that had formed her, would not inherit them, that if a brother should never draw breath for longer than a few weeks it would descend, lordship and seat, to her uncle.

How often I must have heard this echo: “Darling, look at what your uncle has sent you!” And Rhaenyra would come forward, either flying forth with an excited clap of her hands, if it had not been long since said uncle’s departure, and as if despite her tantrums and sulks whenever he dared to leave her presence she was somewhere glad he did so it might enable these sign of his adoration, these offerings of homage sent back to her from afar in crates footmen must be sent for to pry open the lids of, to lift out of the straw the smaller containers that had conveyed the submitted treasure safely for her inspection, as she raised her entwined hands to cradle beneath her chin, tapping her lip with a considering forefinger; or, if he had been absent for what she determined was too protracted a duration and she demanded he present himself to worship in his person, with a sullen shuffle, a dull, resentful glare, crossed arms that rejected all attempts to pass over these additions to her hoard for her perusal, emphasized by a pout.

Up from the packing came candies in their tissued honeycombs; velvet and silk and lace for ribbons and sashes and handkerchiefs; a music box where a Lysene dancing girl forever and never whirled away her veils to a mechanical tune; to hold the emeralds and rubies and sapphires and pearls to encircle her slender neck and slight wrists, to bering her stubby fingers and stud her tiny ears; and altogether stranger gifts, or so they must have struck me in the beginning—fossilized dragon scales preserved in a slab of shale, for example; or an antique dagger (the tantrum after this was quickly removed from her possession was so frightening it had me wailing), or one of the stunted firewyrms that still lived in the Doom, brought back from the expedition, though it died shortly after (Rhaenyra’s wails so heartrending in their grief for the ugly, loathed creature it had me weeping); but more than anything there were the books, books and books and books, and the dolls, of cloth and wood and wax and porcelain.

A fellow worshiper attending the observance of this ritual might conclude that it was fitting the priestess of this bizarre cult should be a girl-child after all, because, with one or two idiosyncratic touches allowable to a child with liberal guardians who believed that an interest in history both natural and social did not go amiss in the education of female offspring, they were exactly the presents of any spoilt little girl. It was only after more sustained service as acolyte performed in the management of this treasury that the oddity of these donations—or rather, the use made of them—became clear.

A glut of gifts, profligate, with no rhyme or reason or guiding principle. As if every morning, this uncle—I imagined this before I ever met him—woke after his corrupted nights (my father had tried to find him various forms of employment to set him up in the world and give shape to his days, as he himself had yearned to do as a younger son, but he not acquit himself well, scorned my father for his assistance, resented him for the preference his brother showed to him above his own feckless self, and rejected the company of his family and residence upon his native shore to fritter away his inheritance in a dissipated restless wandering) and walked through the great cities of the world with his only thought what the brilliance of modern civilization might produce for the delight of doted upon nieces and considered the day a failure if he had not acquired at least one, but the presents that seemed most exceptional to the larger mass actually provided the key to decode a scheme that was actually the reverse: it was the glories of a past civilization, whose remnants his self-imposed exile led him to sojourn among that apparently spoke to him, endlessly, of a small girl left behind.

This passion that niece and uncle shared—or rather that he had helped breed in her from an early date—was not on its face remarkable. Enthusiasm for the study of ancient Valyria, its history and science and art and literature, was widespread in Westeros, where the achievements of that vanished empire were acknowledged to be of so towering a stature that despite the slightness of that polity’s impact on the annals of our realms in vulgar political terms, its influence on the course of the world’s destiny merited a debt of appreciation be paid by all educated men and women. It rose to what could without exaggeration be named passion, for many, to near mania in some; what had been a trickle of travelers to the Free Cities across the Narrow Sea had swelled to a tide that flowed unceasingly to deposit my countrymen and women on those shores where the more material eternity of the flowerings of its culture could be encountered.

Professorships endowed; expeditions to the Doom funded; museum wings dedicated. Highborn children copied the foreign characters out of primers and learned poetry in challenging but suddenly astonishingly comprehensible syllables by heart under the supervision of their tutors, and any child who could acquire myths retold to improve tender years from a bookseller’s stall might have their imagination stimulated by the exalted past. This being the case, it required even less explanation for why a little girl should demonstrate such interest, when that girl was a Targaryen.

They had brought the last dragons to our shores, millennia ago, where they had shortly after perished—but the last dragons (creatures whose existence was a matter of doubt, in a latter, more enlightened age, until the energies of that enlightenment had in their turn used scientific principles to prove their facticity from the bones to be found plentifully through the whole span of the world) had died on Dragonstone, claimed by the Kingdom of Storms. After this the Targaryens had sunk into relative obscurity as another noble family swearing fealty to House Durrandon, often prominent, if not always creditably so, in the affairs of the kingdom but far fallen from the dragonlords whose acts had directly and irrevocably shaped the course of human events. All that remained was the almost mystical, eerie aura of dynamic relics, of an access to what was lost conveyed physically by the silver hair and violet eyes that still bred strong from the proudly cultivated separateness that contributed its part to the mixture of aversion and fascination that made any mention of them thrum with its unique peculiar tension.

Lord Viserys, having deferred from the vigorous political life of his predecessor, devoted his days instead to the study of Valyrian antiquity. He corresponded with scholars, and scholars regularly presented themselves at the gate on the bridge that was still the only way onto the island, and were admitted regardless of their pedigree or credentials to examine whatever particular tome was the very key to their researches which could be only be found there—although only to be examined under the eagle-eyed surveillance of a Dr. Mellos Melcolm, who was in residence as physician to its delicate lady but also had assumed management of the library—as long as they could conduct an elucidating conversation on this cherished subject. For the library at Dragonstone had one of the most impressive collections of Valyrian texts in the world, and crates sent from Volantis addressed from brother to brother were also carried into the Great Hall and pried upon by footmen to reveal to their eager master fragile manuscripts to add to this already priceless archive.

The streams did not cross. Occasionally Daemon would append a note to a manuscript of particular antiquity or interest, urging his brother to show it to his daughter, and that was a great treat for Rhaenyra, to be perched on her father’s lap, Dr. Melcolm opening tome too huge to hold in the hands on the table in the library appointed for this purpose, and Rhaenyra leaning over to look at the colorful illuminations as her father carefully turned the pages, paint still bright even on browning vellum so fragile it looked as it they might crumble to pieces any moment, so conscious of this special moment of attention she was unusually heedful of the prohibition not to touch. But although a man who sent a girl of five daggers and whips as gifts would hardly have compunctions about the risk to the historical record posed by gifting her singular manuscript copies, from her uncle Rhaenyra received only printed books, and this was because her most generous devotee understood that it was not the book itself that interested her, its age or its rarity but what was inside.

From the bottom of the crate, beneath jewels and dolls, she would unearth the latest text. They were not books for children, and at that stage she could not read the ones in Volantene or Pentoshi. She would soon enough, and eagerly she consumed the words that described for her the palaces of the dragonlords, built high into the heavens from shining dragonglass, with their rooftops large enough for dragons of hundreds of years of age to land safely upon, the slave markets of Draconys, the Anogrion where the conquered were sacrificed on great altars, their blood drained caught in bowls so that the blood mages could work it into magic spells—at least in the Old Valyrian epic that was the first complete narrative in High Valyrian that we and all other school children read. In other households but this one the most exciting parts might be redacted for moral reasons, for it told the mythic tale of a decades long war with Old Ghis, written down many centuries after that shadowy conflict is estimated to have taken place, where the gods helped and hindered dragonlord heroes, one who stole away his brother’s wife (who was, of course, the sister of both) so the betrayed brother sacrificed his own daughter to have blood of the dragon powerful enough to call down a great curse…

Even before we could read that or any other, we looked at the illustrations. The reproduction of a black blood-draining bowl excavated from the city Tyria, where a scene from the poem where the sister married her elder brother, gazing back over her shoulder at her younger brother on the steps of the temple the wedded pair have just exited in fear of his longing or in her own, we could not decide, was worked in red. Hours Rhaenyra could study this: the fall of the bride’s tunic, the elaborate coils of braided hair wrapped around her head, the dragons the couple walked toward to mount for the traditional last virgin’s flight, the slave musicians strumming a lyre and beating a drum in perhaps the same bridal hymn whose remaining fragments it illustrated. Or the one of the friezes from a merchant’s mansion in the same city, which depicted the sack of a city which was supposed to be the final destruction of Old Ghis, but which suspiciously looked like the contemporary Valyrian city where the home whose dining room it decorated was located: the dragons swooping rained down flame, but almost as an afterthought to the lovely sweep of their wings as they soared across an incongruously fine evening sky, the artist obviously having desired to use up a large shipment of Tyroshi purple to flaunt his patron’s wealth, and loathing to obscure it with a humble mix of black and white for smoke.

These and other famed artworks were familiar to both father and daughter. Some of the features were sources of common perusal, I suspect: the dragons, of course, and the temples with their lurid, macabre fascination. But in an imagining of how the Anogrion might have appeared, based on extant texts, Lord Targaryen looked to the ornamentation of the pediments, to ensure the greatest accuracy in his great project, which was an immense model of the city of Valyria, recreated down to fine detail in plans he had various artists in succession draw up to his specifications, based on the research he pursued. Rhaenyra looked down below the draconic grotesques, to the line of the garments the priestesses wore as they held the knife above a bound captive on the steps. Her eyes bore into the pipes a flute girl in the crowd played, her head cocking to the side as if she listened to some inner silence hard enough, she would be able to hear its ancient rhythms.

She wished to live Valyria. The other most common gifts, the dolls, were the first clue, her first opportunity for trial, before the addition of me allowed for an expansion of her horizons—a vision of living it in herself, which needed a companion. The velvet and silk and lace, whatever their intended purpose, where made at her instruction into tunics and gowns and mantles to clothe dolls stripped of the latest crinolines they came out of their boxes in to transform them from fashionable Oldtown ladies into dragonladies, priestesses, Rhoynish captives.

One not familiar with the fate of these expensive gifts, on watching multiple of these unboxings, would begin to wonder how even such a nursery as the behemoth of Dragonstone must contain to nurture its young would have room for all of them. I wondered too, jealousy. I had no lack of toys, but even I was stricken by envy at the sheer embarrassment of riches on display. Perhaps not that first day, but shortly thereafter, Rhaenyra grabbed up one doll—one of the priestesses in her black tunic and red hooded mantle and high-laced sandals—thrust another into my arms—a shoeless Rhoynish captive in a white smock—and, evading Septa Marlowe with her usual ease, by our entwined free hands pulled me out into the sun.

On a stretch of seashore hidden from all eyes by one of the large black rocks that dotted the sand, chosen, however, for a particular black stone worn shiny and smooth by the tide when high, but revealed when it was far out as it was at this hour, the sun making us squint when flashed into our eyes from the silver pools spangling the muddy expanse.

There was a ritual, which she had worked out in fine detail during many lonely rehearsals. First, we must adore the dolls into submission, both mistress and slave. This was done by sitting on another rock, our feet dangling into one of the pools, jabbering away at nonsense childish business, pretending the dolls in our arms weren’t there, to let them know they weren’t real, as we brushed their hair, and tweaked their garments, and cradled them in our arms as we ran our fingers over their tiny, exquisite porcelain faces, and gazed adoringly into their shiny glass eyes. Anyone who has been a child, and while lying awake sleepless in the dark in a bedroom shared with dolls, or stuffed animals, or toy soldiers, or anything with eyes that might look, has hoped their daytime incantations have been sufficient, their stultifying love powerful enough to pet and kiss and stroke into a stunned daze strong enough to last the night’s terror.

Then, we must adore them back into life for us. We must stand them up in our laps, and chatter at them, and let them chatter to each other through us, and sing them little songs, and tell them how beautiful they looked, and flesh out their backstories in exhaustive detail (the dragonlady had entered the temple after being disappointed in love; she would have her revenge on her fickle brother when she had the enslaved Rhoynish princess he’d fallen in love with when he’d captured her as booty on campaign included among the next round of sacrifices). Anyone who has been a child, and on leaving their room in the morning has left behind dolls, or stuffed animals, or toy soldiers, has when returning from some outing and going to their room to change for luncheon, paused at the door to their room with their hand on the handle, hoping when they twist it open they will find anything with limbs that might move alive and busy about the doings these things we so imbue with our life must surely occupy themselves with when we are not present. Or perhaps it was the other way around—that would perhaps make more sense, but in my memory this was the formula: uneasily subdued, but qualifiedly alive.

Only then could her preferred game at that stage again. She told me in terrifying detail about the blood sacrifices that the Valyrians believed had made them master of the world, of the powerful priestesses who oversaw the slitting of the throats of hundreds of captives so the blood ran down the altars in waves, who slathered their bare breasts in it and ululated songs filled with the roars and whistles of dragonspeech in thanks for the victories that had brought these captives to them, and to call forth more victories, and yet more sacrifices for the gods. Then, called by the scent of the blood, dragons would thunder down from the sky to bathe the corpses in fire, and consume the most fortunate of the dead.

I wonder if my father found it ludicrous or obscene, when he once caught us at it while out for a hack. The first time I was roped in as a conductor to the rite, I wavered between nervous giggles and tears of terror, knowing I must smother both equally if I was to pass muster. The second time was easier, and by the third I could not have imagined feeling amusement or fear. We smashed the doll’s faces in with a solemnity and fervor that, as I picture myself as I am now, looking down on Rhaenyra and my small self, I cannot decide whether I find amusing or sickening. There was no blood. We gathered shards into a bowl secreted in a hollow of the looming outcrop for that purpose, and then dipped it in seawater warmed by the sun, and slathered our faces in it, and pretended it was blood.

This game had been her compulsive, obsessive fixation for a good while, I gathered. Once I was entered in, it expanded out. She had tunics made for herself, and me as well, and insisted upon going about in them. Even the year she died, she would often shun corsets and petticoats for this garb: tunics of gold, like fire, for a maiden of a dragonlord family, black, like smoke, for a matron, red, like blood, for a priestess. These were the only colors she ever wore even when she submitted to modern shape and line. The white gown with embroidery of the most up-to-date fashion of 1852 I painted her in, shipped in a long box from Oldtown, worn because she thought our new drawing master Mr. Cole might like it, was a rarity.

With my advent in her universe, a living doll expanded her capacities. I too would lie on the black rock, chill beneath my white tunic, and with the edge of a broken shell she would prick my chest, where an adult was less likely to take note. The greater powers of childish imagination were sufficient for the rest. I went limp, my eyes fluttered closed so the sunshine through and painted the back of the lids red with the blood in my veins, so I could see it, what she wanted me to see—the blood washing down the stone, enough blood to paint her face as red as her tunic, and my acquiescence, my entering in to her playing at power, was somehow power enough to magnify the miserly drops she dabbed at her cheeks, and scrubbed out with sea water before we returned home.

I thought this rite of blood had initiated me, but after several months, I learned there was another that I must undergo for full admission. Early in the morning, before anyone but servants laying the fires stirred, when the entire island was shrouded with thick fog, she shook me awake. She gave me a couple of fat wax candles to carry, and a book of matches for my pocket. She held the hilt of a knife that I could tell was sharper than any we were allowed to use in her fist, and our shoes swung by their laces from the same grip. She always distributed our burdens so one hand each remained free to clutch at the others. Sneaking down the stairs in our socks, out a side door where we put our boots on, shushing the other’s giggles.

The giggles vanished from her face after that, as a solemn look stole over her features. Mine disappeared as well, as the sunless morning was chill, and the smothering fog made my small form a miserably damp one within minutes, and I was pining for the chocolate we would have for breakfast, and because the walk to the destination she would not reveal was arduous, being long and entirely uphill, and my legs tired quickly as we clambered over rocks upward toward the peak that was still known as the Dragonmont, though the single generation of those creatures that had made their nests and laid their eggs there before dying out mysteriously was so far in the past.

We arrived at a cleft in the rock that it would be exceedingly difficult to find if you did not already know of its existence, obscured by a jumble of surrounding rock who I only noted because they provided a shelter from the wind. In a dry crevice, she placed the candles and the knife, and took my sweaty palms in hers. I wanted to laugh, she appeared so uncharacteristically serious, but, and even now I can’t decide if this was fortunate or unfortunate, if it doomed me or saved me, if it marks me worthy or damned. For there is no doubt in me that she would have turned back then, if I had.

She informed me that what she wished to show me was very special. That only Targaryens could see it. I nodded glumly, accepting, if peevish that her desire for my company had set me on such a pointless trek. I plopped down on a rock, quite content to wait for her, or fearful that if I gave vent to the true extent of my irritation with her she would have her revenge. In such moments, the dolls were brought out once more, and she would talk to them of me as if I was not there, saying that wasn’t it a shame Alicent insisted on being such a bore, until I had to demonstrate a sufficient spirit to win back her approval by seizing the usurper and smashing her face against the doorframe while Rhaenyra screamed murder as if she herself was victim of unspeakable violence.

When she saw my dejected, exhausted slump, she laughed, poking her tongue through the gap in her teeth as was her habit. “That is why you must become my blood sister,” she explained. This was the purpose for which she had brought the knife. On the slimy moss of the rock she laid our two skinny wrists side-by-side, and tossed the blade over to me. I shook my head in a sick panic. I tried to press it back into her hands. “You must,” she insisted. “You must cut your palm, enough to draw your blood, and then I will draw mine, and we can mix ours together, and we will be blood sisters.”

“Please, Rhaenyra,” I begged in a pitiful whine. “You do it for me.”

I was nearly in tears, nauseous with misery at how I was about to prove my unworthiness with my squeamishness. An eloquent noise of disgust passed her lips, and spurred by fear and fury—why must I do it first—I grabbed up the knife and slashed down, aiming for her palm but wild with my welter of feelings dragging it across the inside of that bared arm instead. Rhaenyra yelled in outrage so that I thought they must surely hear us back at Dragonstone and send someone to drag as back, and then laid into me, saying that I might have the rest of them tricked into thinking I was an angel who could do no wrong but she knew I was a foul little beast, and then scrabbled with her dripping arm for dropped instrument and slit me open with her own enraged hacking motion.

Then she grasped me by the hand. We interlaced our fingers and pressed our entire arms together so the slits we’d carved in each other’s fleshed kissed, smearing our blood together just as she’d prescribed, until we could have not said whose stained us where, whether our own caused the greater damage or the other’s. She had her elaborate rituals, chanting Valyrian prayers of her own devising, but for this momentous occasion apparently the blood was sufficient: the blood, all, to which the addition of mere words, even in that tongue so suited to the rites of blood, its shedding and redistribution and refashioning, would have debased it. We stared at each other as the wind whipped our unbound hair across our faces, into the salt-tracks of the angry tears had carved across our cold cheeks. She simply kissed me once and said “Haedar,” and though my grasp of the language was at that point far inferior, having started my tutelage once we had a tutor in common, and never very good, lacking in the practice she had received at such a tender age in its use as a language of everyday living, I knew of course what it meant.

We tore strips from our chemises, and plucked moss from the stone—believing ourselves far more gravely injured than we in fact were, and in need of serious measures to stanch the bleeding that was now the livid, euphoric sign of the risk we had dared in our devotion to one another—and bound our wounds, and leaving the rusting blade upon the rock retrieved the candles from the hollow. Taking the hand at the end of my stinging wrist, Rhaenyra led the way. The passageway was so narrow that even tiny girls as we were then had to go in sideways. My free palm dragged along the pitted black stone, because we quickly plunged into a profound blackness that my sight could not penetrate. My whimpers of fear echoed off what I knew with a shiver was not the stone close around us, but some immensity of darkness beyond that I could not see, any more than I could see the bright head in front of me it had swallowed up. There was no way to keep a grip on a candle, with the way we had to shimmy our way forward along the squeezing constriction that left us scraped and bruised and gasping when it finally popped us out into a vastness I could feel, a gusting breeze as some cavern of a size that, denied of sight and after the pressure of that tight damp entrance, I imagined might be another world within the mount, a mirror to the daylight world without just as large, inverted, opening out forever.

When the candles were lit, I saw the stubs of previous illumination around the burning ones Rhaenyra affixed to the rock with the wax she resoftened with the heat of the new flame, like the fragrant mass of melted tallow that formed in the Starry Sept, when we went by train to visit Uncle Hobart and my brother, the remnants of prayers for the dead. Rhaenyra fidgeted during services, pulled faces, could not remember her prayers. One girl, and yet so many visits she must have made to have formed this waxy range with its heights and valleys, to do honor to her dead.

An incredibly well-preserved dragon skeleton, gargantuan in size, its skull alone several times our heights. I squeaked when I worked up the bravery to raise my eyes from Rhaenyra’s preparations to see what they were intended to allow me to see. How many times she must have come here alone, how familiar a routine and a sight. And yet she was weeping, silently, a flow of tears from her eyes but her features quite placid, not twisted with grief. I emitted some noise of concern, and she glanced at me as she stood up. The rage and glee from earlier was gone. She did not appear sad, as I usually found her sadness: a large thing, trapped in her diminutive frame, demanding attention.

“It makes me so sad, that they are all dead, I can’t help it.” she said quietly, as if it was a despair larger than human expression, that could not be contained in her body at all, even uneasily. She must come, and weep, and do as she now did, an odd dance of her own devising, her outspread arms like wings. Thinking back from my present vantage I should be overcome with what a ridiculous sight this was, a tiny girl before the dragon skull flapping her arms about and making mournful dragonish sounds with a ludicrous solemnity. I did not laugh then; I do not laugh now.

-

We entered the dying of childhood, which is simultaneously the birth of womanhood, in these days a much longer span than formerly, a slow dying and protracted birth, designated girlhood. Events occured which murdered pieces of the child within us instantly, a withering of vital parts that left the whole alive but aching, twisted and ugly, and delivered us as malformed adults, incapable of conducting a productive or dignified existence. Which is to say that our mothers died.

But we were not yet women, which was a separate matter, and would not attain that state until we married. We understood we must wait for others to decide our fate, and although we had always known that was the case, and some portion of us felt our own incapacity in the dependence of our recent manglings and the irreplaceable care whose loss precipitated our predicament and made it the more urgently necessary, and yearned for guidance, our minds remained untouched, and were condemned to know that even if we must resign our keeping to others considered wiser, our own intelligences could not help but bring the force of rational analysis to bear on the arrangements in draft and our spirits revolt at the results.

Our mutinies were different. Mine, an entirely inward resentment, quickly anesthetized by temperament and habit to a soothing, dread-laced inertness besides. Hers, enraged, needling, disturbing, unburiable. It made sense this should be so. I would pass from her hands to another’s. This too we had always understood. She had been allowed to dictate our lives—at least as viewed from my petty perspective in light of what it took to be the important details, like what games we should play, and on who we should bestow the favor of our liking and who we must snub, and what colors we should wear, and whether we should confess to a wrongdoing (always vetoed), or resort to stratagems of deception and concealment, which of course followed on whether we should venture to defy a prohibition in the first place (always forced through)—when they were not of much consequence, or so the structuring theory of child rearing seemed to run for Lord and Lady Targaryen. It fell to her bereaved father as her sole remaining parent to begin to realize the error of which all the most sophisticated manuals on parenting sound children would have gladly informed him, about the poor effect worked upon the moral character of those offspring granted too much their own way.

My father, by contrast, had taken pains to make it clear to me, if not in so many words, that I was only on loan to the court of a princess of her own minute, ephemeral, and inconsequential kingdom, as maidens of old trained for their later noblemost services by their virgin thrall to a grand dame. Or I had been permitted to be her doll, safely held in store by assurance of the inanimacy of expectancy, and at the appointed hour, he would breathe the breath of life into me, vivifying me as his daughter so he might give me as wife.

The time was coming soon. Not so soon; we were only fifteen. Rhaenyra died within a year of her mother: fifteen. But we could glimpse it on our horizon—time that can be apprehended by all the senses, as autumn storms could be observed moving in out of the Narrow Sea and over the waves of the Blackwater, darkening them to slate trenches, chopping them up to white heights, toward Dragonstone, and felt in a pounding of the skull, a tightening of the skin. Time, which had seemed infinite, like the depthless blue of an autumn sky, was bounded.

Perhaps you are surprised at the account I provide, at long last, of your sister and our shared infancy. You might reasonably be assumed to expect reveries on the confession of girlish secrets and fears—while walking on a spring day in Aegon’s Garden—hearts that in the trusting whispers of youth have erected no barriers to the free entry of the other so their contents gush forth—beneath the bedclothes long after they should have been asleep—mingling their outpourings till they are as one that beats in two bosoms, a union sealed only by the passionate kisses and warm presses of hands—at the fringes of a ballroom where the churning whirlpool of dancers have cast them up together by a chance that strikes them as miraculous—that must speak the deepest affections with every part of the body. There are anecdotes I could tell, I suppose, attempting to capture and transmit her spirit and what it and mine knew together.

She wished for a little sister each time her mother was brought to bed with another child, when the entirety of keep and lord-dom included a son for Lord Targaryen in their prayers. She never said as much, but I knew she wanted a little sister because a little brother would be born as a symbol of her predestined exile. It galled, as she rode about the island in her black-and-red riding habit with the eventually acquired silver-handled whip at her belt, well-known and well-beloved by all its inhabitants, who swept off their hats and waved handkerchiefs at us from where they walked along the road, how every stony track and dusty path leading to every remote bay and rocky promontory, and every sparse wood with every green-gray glen and every hidden cave would not be hers. Daemon, known first as adored uncle before she understood him to be her future banisher, was, if not never resented, at least only victim of a fitful bitterness that manifested, when piqued by some perceived slight of the duties by her she prescribed, as pointed needling about how she longed for the day she had a brother, and they’d need not have to deal with him. She treasured, in her earliest years before the reality of the present situation was fully comprehended by her, a dream that perhaps Daemon was the way to secure her home permanently, if only like Visenya she could continue to ride about the island in a black-and-red habit with a pistol at her belt, exacting the rents, because even at that advanced date the Targaryens had held to their obscene endogamy, and she had married her brother, and been Lady of Dragonstone.

She thundered down the sands as fast and fearless as any man on a golden mare she’d named Syrax after some ghastly Valyrian goddess of strife, a wild Dornish sand steed bought by Daemon at the Rosby horse fair and brought back to Dragonstone that she’d snuck out to the stables and broke to saddle at the age of seven, and her uncle had smiled while others gasped, when she rode into the courtyard, displaying the bloody cavities left behind by two missing baby teeth in a broad grin, and at the exclamations about how it was a wonder Rhaenyra had not found herself kicked to death by the she-demon brought into their midst, laughed and said that his niece had lost nothing she would not regain, and that was another few months of moping at his swift departure and continued absence we were to endure, as he was punished for having done it on purpose.

She had a predilection for sweet things, and would have eaten only cake if left entirely to her own whims. She followed newspaper accounts of the archeological expeditions that set out from Oldtown to the Doom of Valyria and were slowly excavating to reveal the immense buried capital and surrounding heartland of the empire as eagerly as her father did, and would rhapsodize over dinner about joining them, about being the one to oversee the workers as they finally dug away the compacted volcanic ash and reveal the Anogrion itself, one of the first eyes to see the place where her ancestors had worshiped in a thousand years. I could picture her riding Syrax among the open pits revealing palaces and temples and markets, her silver-handled whip at her belt. This would be greeted by indulgent, dismissive laughter by the company, and I would watch her shrink, and wonder at the fact that no one else seemed to see a scene my mind’s eye painted so vividly.

(So, you see, in the end it must return to the dead.)

She adored me. I never could make sense of why. She enjoyed my beauty, certainly. She was proud of having such a beautiful friend on her arm, as if it was an accomplishment of her own personal achievement. That Rhaenyra should enjoy a beautiful friend, that it was a delight she in some way deserved, resolved the mystery of her enjoyment of my company—a girl known for her nerves, who wept herself sick at many of the schemes of entertainment her companion concocted, who primly scolded her for failing to do the exercises assigned us by their septa, who piously said her prayers every night before bed—well enough for most everyone’s satisfaction. Not mine. I knew it was inadequate.

I think that it was exactly this—that in the midst of dinner, with my eyes open, laughing politely along with the rest—I was painting the image of her, I was seeing it. Rhaenyra spurring Syrax in a gold flash across the black rock, reining her to a halt at the side of the pit, barking orders. Rhaenyra in her tent, a brush made of rabbit fur in her hand, loosening the caked sludge from the face of an icon by lantern light. Rhaenyra in Volantis at the museum to which much of the finds were brought, somehow sneaking her way into the chamber where they kept the dirty things, like statues of dragons with enormous phalluses and the writhing, nude forms of a humans male and female with gaping orifices, caught by the scruff in the wyrm’s jaws. I saw it. She became absorbed in the detritus on her near empty plate, mouth working, and then looked up at me, and saw me seeing. She let me see. For this I adored her.

When she died, I was not at Dragonstone. I had gone to my father, conducting business in town, to his displeasure. She had been ill for weeks, feverish and tired, sleeping a lot during the day, restless at night. But not severely, not in a way that had Dr. Mellos worried. She suddenly took a turn for the worse, her fever spiking, unable to stay awake for more than a few minutes at a stretch until finally she did not awake again at all. She kept calling for four things, over and over, in those shortening spans of consciousness: uncle, Syrax, cake, Alicent.

To speak of her truly would bring her into time. That was a cruelty and a kindness I could not find the mercy or viciousness within me to perform. I felt enough hate and tenderness to banish her from time, of such depth that it could only have been conquered by a love and resentment that shrunk in horror from condemning her to or reprieving her from it.

I can only leave with the image of her joyous despairing dances before the bones of the dead, the kinetic whirl of her living homage with her young body offered up as the adoring private testament to the dying of ages, for only me to bear witness to. They found the bones when they tore up the mountain, when they dug the mines: a donation that was the crown jewel of the wing of the museum of natural history that will bear your father’s name once completed with your grandfather’s money.

-

I married Viserys Targaryen at the age of eighteen. My father received a letter from our old governess Septa Marlowe informing him that Rhaenyra had died. We returned to Dragonstone, and I did not depart again as Alicent Hightower.

An understanding was reached quickly enough. Lord Targaryen was shattered by the death of his wife, son, and now daughter in such short succession. He would need a new wife—no matter what he said to me in the immediate aftermath of his wife’s burial about how he could not imagine ever marrying again, because he could not fathom finding his wife’s equal in sweetness or sense in any other of the female sex, my father told me with tinge of scorn that Viserys was not a man who could do without a woman long.

I was a dutiful girl, and this was what my father wanted for me, and my mother had instructed me on her deathbed to obey my father in all things, as he was godly and wise and her lord and guide and would do exactly as she would want for my good and happiness. I was also not a stupid girl, and understood the business considerations that made a grandson the heir to Dragonstone and its mines an enticing prospect. I liked Viserys. Although much my senior in age, I believed myself to be older than my years, possessed of a seriousness and lack of girlish charm, at least among young men, that I feared acted as an antidote to the beauty I knew I possessed in equal measure. A man of middle years and retiring habits would appreciate and honor a wife who had no taste for the whirl of society but was learned enough to follow the studies which were his favorite subject of conversation…

-

…but when they placed your brother Aegon in my arms for the first time, the accompanying first thought was not of the fact that I had succeeded at last in procuring what had long been the dearest wish of my husband’s heart, a son, an heir of his body for his ancient line and a worthy next master of Dragonstone, and the triumph which that ought to engender, but a conviction of failure which oppressed me so that I wept. In successfully giving Viserys a son, I had failed to give Rhaenyra a sister.

…she had infected me. She had poisoned any chance of happiness I might have had as a woman, as a wife and mother, some element in her blood…

-

[O.O: The preceding fragments are, firstly, a page of which the bottom half appears to have been burnt away, and secondly, two fragments from what I guess is another page nearly entirely consumed. From the way the narrative resumes on the following page, it appears a significant portion of the manuscript following this was successfully burnt.]

-

(Scribbled in the margins at the top and sides of the next pages, unburnt…)

I intended to tell it all, to give a full account of my life to you. To at last be honest in writing as I could never be face-to-face. To give you whatever wisdom my life might provide you for your time. I looked at you and saw a girl with hair of her shade and the texture of mine. You are very like me, and nothing like me. You are very like her, and nothing like her. The remainder is, I suppose, your self. You too evade time among your moths and spiders. So many thousands and thousands of their successive lives are lived within a span of one of ours, you told me once, so to them we would appear immortal, and on them we have a perspective of their doings like gods. She would have poked her tongue into her cheek and glanced at me sideways to see what I made of this blasphemy. As with all your statements, it did not seem to occur to you that there could be anything objectionable in saying just what you thought, as long as it struck you as true.

The table-rappers that have of late become so popular among us say the dead do speak. The soul lives on after death to learn transforming truths to impart to the living if only we might listen, and if there is one of themselves, a special person of sufficient spiritual elevation, to act as the medium for the dead to communicate through. I thought I had no need. I spoke to the dead through the gods. I was right, and wrong. I could accept no lesser medium. I could accept no medium at all. I must speak to the dead, face-to-face. I become the medium in the recording now. There are things only the dead can say. I might have thought only the living can tell about the dead or what it is like to live on after the dead have gone, but it turns out the dead can speak on that too, what it is to die past life, that they are not the same thing, and yet the living past the dead now seems to be the pale shadow of that other to me.

I began to think of girlhood again. I had never really stopped, but when you entered that most risky stage—fourteen!—it weighed upon my mind more heavily than ever. Girls were everywhere. You in the schoolroom, bent over a slate with Aemond as he helped you with your High Valyrian grammar. Aegon, who should have left it but had been sent down from school, wandering through in his boredom, smelling of the liquor the grooms returned to brewing in an empty stall each time the enterprise was busted, leaning over your shoulder and tugging at your braid, making a remark I could not hear from the door where I had flown up after him to drag him out by the ear but which I could see made your jaw clench and your hand tighten on the chalk, and had Aemond springing up shouting at his brother.

Rhaenyra—fourteen!—in her portrait.

A maid servant named Dyana—fourteen!

Cassandra Baratheon, the eldest daughter of the most prosperous knight on the island, who I invited to Dragonstone for a fortnight—to see if she might do for Aegon, as I knew I must begin attending to having you all settled, one by one, and because you had never managed to make any bosom friends—who you barely spoke three words to, and sent home less than a week into the stay because she’d fallen ill.

Dead girls. Dead dismissed maidservants. Dead girls everywhere, a mysterious wasting illness that turned them gaunt and hollow-eyed and wracked with shivers—one serving girl in the nameless inn by the wharf with the dragon statue, one barmaid at the tavern across the street. Half-dead Cassandra, so voluble at the start, leaving wrapped in furs in the carriage we were sending her back to her father in, silent. It was no wonder I began seeing your sister, twenty years dead. Behind a curtain in your father’s room as I sat by his bed reading to him, just after he’d begun to snore. At the door to the Great Hall during supper. On a bench in Aegon’s Garden when I walked fretfully of a midnight. I thought I was going mad. It had long seemed my fate, that her unburied memory would return to torment me out of my sanity.

A dead girl in my bedroom, appearing behind me in the mirror as I brushed my hair, after I’d slipped off my robe, but before I slipped between the sheets in my nightgown. A dead girl, speaking to me.

-

“That spring after my mother died I often had trouble sleeping, as you perhaps remember. Or perhaps not. You slept so easily, or so I believed. When my miserable thrashing disturbed you in the bed we often shared, you would swim up from your slumber just far enough to irritably murmur, “Rhaenyra, you toss and turn so…”

But it never disturbed you so much it could wrench you from whatever dreams had you so in their grip that you slipped back beneath the surface of sleep almost immediately, and you showed no signs of rousing when I sat up, and gazed down at you in the shaft of moonlight streaming through the window.

That lunar brilliance of Dragonstone, so pure and strong, made the lineaments of your brow and throat glow with a shocking brightness and leeched all color from your hair, turning your fiery curls into a dark mass writhing across your pillow, against which the familiar, beloved contours of your pretty face were turned stark and strange, and the tendrils snaking down to flow across the breast whose slight movements with your breath were the only sign you were a living girl and not a effigy carved in marble upon a sepulcher.